From £2,920-a month at Hyde Park Corner to just £324 in Hatton Cross...

2015年9月29日 星期二

2015年9月28日 星期一

separatist movements around Europe

#Dailychart: Catalonia's separatist movement falls short of an absolute majority, but it's overall win was watched intently by other fervent separatist movements around Europe http://econ.st/1MBjtih

巴黎首推無車日減污染

去年佔領運動期間本港部份馬路受阻,導致汽車流量大幅減少,意外地為中環、銅鑼灣和旺角帶來短暫的清新空氣。一年後,法國巴黎為改善空氣污染問題,首次實施了「無車日」,讓民眾可盡情在馬路上散步。

在周日巴黎的香榭麗舍大道上,平日繁忙的交通突然消失,馬路沒有了汽車的噪音和廢氣。市民紛紛走到街上輕鬆散步,有小孩在馬路上踏單車、玩滑板,令這條著名的大街變成一個休憩公園。

2015年9月24日 星期四

基隆北方三座離島:Pinnacle I., Crag I., Agincourt I.

基隆北方三島的洋名字 原來都是150年前英國艦長取的

英國艦長將彭佳嶼洋名命名為台灣的阿金庫爾 希望打仗能以寡擊眾

江則誼/編譯 2015-09-24 08:10

基隆北方三島花瓶嶼、棉花嶼、彭佳嶼被標示成奇怪的英文名字,原來是牽涉一段150年前的國際關係故事的。(截圖自石井望教授《歐洲古圖為證》一文附圖)

基隆北方有三座離島,由南往北分別是:花瓶嶼、棉花嶼以及彭佳嶼。在斯蒂勒與史丹福所繪製的十九世紀老地圖中,我們看到花瓶嶼的位置標上「尖頂島」(Pinnacle I.);棉花嶼的位置標上「危崖島」(Crag I.);彭佳嶼的位置則標上「阿金庫爾島」(Agincourt I.)。這是怎麼回事?尤其是彭佳嶼,「阿金庫爾」是甚麼怪名字?

在解開這疑問前,先來了解1860年代的歐洲局勢。那時歐洲的英國與俄羅斯正在衝突,1856年英國贏得克里米亞戰爭,暫時阻止俄羅斯蠶食土耳其,逼得俄羅斯只能再次向東方擴張,但俄羅斯東擴勢力很快接近英國的勢力範圍: 伊朗與印度,還趁著清廷與英法聯軍作戰,以調停國身份強迫清廷割讓烏蘇里江以東的土地,順利取得遠東港口海參崴。

對英國來說,俄羅斯再次東擴將損害英國的利益,所以英國政府決定在亞洲扶植一個政權與俄羅斯對抗。原本英國想找中國,但看到清軍戰鬥力大有問題,只好放棄扶植中國。剛好1863年英薩戰爭爆發,日本薩摩藩雖然獨自力抗英國艦隊失敗,卻使英國見識到薩摩藩的實力,所以決定支持薩摩藩,薩摩藩日後成為明治維新的推手,英國也就順勢扶植日本成為對抗俄羅斯的亞洲盟國。

英國為了支援日本這個新盟國,皇家海軍重啟「廣域海洋探測計劃」,派出數艘軍艦前往亞洲,收集英國到東南亞、再經過中國沿海抵達日本的航道水文資料。1866年,皇家海軍小型砲艦「巨蛇號」(HMS Serpent)在艦長查理.布勒克(Charles J. Bullock)指揮下從英國航向日本廣島,沿途進行海洋探測。巨蛇號的船醫兼自然學家卡斯伯.科林伍德(Cuthbert Collingwood)根據這趟旅行的所見所聞寫成一本遊記:《自然學家漫談中國海岸》(Rambles of a naturalist on the shores and waters of the China Sea,1868出版)。

該書第八章<福爾摩沙東北方諸島>描述1866年6月巨蛇號從基隆港出發,往東北方航行,準備調查基隆東北方約180英哩的新兵島(Recruit Island)與洛利礁(Raleigh Rock)的確實位置。新兵島可能是釣魚台列嶼中的赤尾嶼,而洛利礁可能是赤尾嶼周遭露出海面甚高的礁石。巨蛇號出海沒多久陸續發現三個小島,就是花瓶嶼、棉花嶼及彭佳嶼。艦上人員們對這三個小島所知極少,除了彭佳嶼已經標在海圖上,其他兩個小島從未在海圖上出現過,所以經過例行地探測小島四周的海域後,也登上棉花嶼及彭佳嶼實地觀察島上狀況。從該章內容來看,布勒克艦長可能在這趟任務中為三個小島命名。花瓶嶼外型如針突出於海面上,命名為「尖頂島」、棉花嶼四周大部份是懸崖峭壁,命名為「危崖島」、面積最大的彭佳嶼則以法國鄉村「阿金庫爾」命名。

阿金庫爾在今日法國加萊海峽省,1415年英格蘭國王亨利五世曾親率軍隊,在這裡以寡擊眾打敗法蘭西大軍,因而以「阿金庫爾會戰」著名,六百年來在英國家喻戶曉,莎士比亞戲劇《亨利五世》裡最有名的一幕就是亨利五世在開戰前激勵英軍的演說。

其實,十八世紀中業到十九世紀初期歐美各國的海圖上,彭佳嶼大部份都標為「Pong-kia-chan」,也就是「彭佳山」的發音,康熙年間製作的《皇輿全覽圖》就是將這座小島標為彭佳山,歐洲各國繼續延用。而英國海軍可能為了方便海員們記住這座島,才將彭佳嶼「重新命名」為阿金庫爾島,因為阿金庫爾對英國人來說意義重大。既然英國這個海上強權這麼做,歐美其他國家也就順勢附和。自此之後將近150年,歐美各國的海圖上,基隆北方三島大都標示著布勒克艦長當年所取的洋名。

參考新聞來源:

《民報》:歐洲古圖為證:釣魚台自古不屬於中國。

《民報》:歐洲古圖為證:釣魚台自古不屬於中國。

參考資料來源:

《自然學家漫談中國海岸》(英文,可線上閱讀或下載電子檔)

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/cu31924024005807#page/1/mode/1up

《自然學家漫談中國海岸》(英文,可線上閱讀或下載電子檔)

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ia/cu31924024005807#page/1/mode/1up

高雄 旗津「彩虹教堂」?

旗津有美麗的海灘與尚青的海鮮料理,近年來,市府團隊努力打造旗津成為觀光大島為目標,從102年開始分階段辦理海岸線修復工程,透過離岸潛堤找回旗津沙灘,讓旗津海岸景色更美、更安全。

「彩虹教堂」是政府與民間合作的成功案例,將效率偏低的公用空間,透過民間資源,改造成婚紗基地,吸引國內外婚拍產業,為旗津海岸公園注入新元素。高雄會更用心打造成一個美麗、幸福的城市,讓更多的人來到高雄、留在高雄、嚮往高雄。

2015年9月23日 星期三

Christ Church Meadow, University of Oxford

Christ Church Meadow is a large area of tranquil pasture in the heart of the busy city, owned and maintained by Christ Church, Oxford and bordering the rivers Cherwell and Isis.

The meadow is open to the public until dusk each day, so if you find yourself with a spare half hour this autumn, take a wander.

日本熱海市樹屋,環繞於 300 年古木之間

[新聞] 日本最大樹屋,環繞於 300 年古木之間

許多人嚮往穿梭於樹木枝枒間,與森林同呼吸,感受與自然共生共存的美好。除了在森林紮營、野餐、健行,享受林地風景之外,若想體驗「被樹木擁抱」的生活,打破自然與人類的界線,不如爬到樹上去!日本樹屋達人小林崇,便是以如此純粹的心情開始建造樹屋的,在過去 15 年來,小林崇建造了 120 座樹屋,去年三月,則在日本熱海市一處度假區,落成了全日本最大的樹屋──Kusukusu:http://www.biosmonthly.com/contactd.php?id=6477

2015年9月22日 星期二

全球只有一個德國(江春男)

司馬觀點:全球只有一個德國(江春男)

德國不僅是歐洲經濟的火車頭,也是歐洲道德的火車頭,這不僅僅是政府的抉擇,也是社會的共識,這次數十萬難民湧入德國,為了分散安頓,全國展開救援行動,估計有2000多萬民眾參與,這樣救苦救難,重視人道的國家,全球只有一個。德國人囗只有8000萬,卻要接納80萬難民,對財政、經濟、社會各方面都造成重大壓力,梅克爾在國際上備受稱讚。美英領袖都對她表示高度肯定,曾經辱罵她的希臘人,這次也對她大加讚賞。

法國的心情比較複雜,它以自由、平等、博愛為立國精神,有「人權的國度」之稱,而且與敘利亞有深遠關係,在一戰之後統治敘利亞長達25年,附近的貝魯特有「東方巴黎」之美名,但是, 法國經濟疲弱,工作難找, 官僚行政繁瑣,公務員只說法文,難拿到居留許可, 難民為之卻步。

德國拿到人權冠軍,法國媒體對此充滿醋意,嘲笑梅克爾像歐洲女王,命令歐洲子民也必須這樣做,並諷刺德國的經濟起飛,都是靠難民的廉價勞動力。

德國的右翼團體對難民充滿敵意,他們發動示威活動,引發暴力衝突。而梅克爾的政敵也對邊提出尖銳批評,一向不輕易流露感情的她,終於忍不住了,她有點激動:「老實說,如果要我為這個發自內心的良好行為道歉,那麼,德國就不再是我的國家了」。

德國拿到人權冠軍,法國媒體對此充滿醋意,嘲笑梅克爾像歐洲女王,命令歐洲子民也必須這樣做,並諷刺德國的經濟起飛,都是靠難民的廉價勞動力。

德國的右翼團體對難民充滿敵意,他們發動示威活動,引發暴力衝突。而梅克爾的政敵也對邊提出尖銳批評,一向不輕易流露感情的她,終於忍不住了,她有點激動:「老實說,如果要我為這個發自內心的良好行為道歉,那麼,德國就不再是我的國家了」。

擔心恐怖份子混入

仇外的右翼團體都以愛國主義為號召,德國新納粹也是如此,近年來穆斯林變成主要目標,這次難民都來自穆斯林世界,他們擔心德國被穆斯林淹沒,擔心恐怖份子混進來,他們挑起種族主義論調。

但是經歷了納粹噩夢,浴火重生的德國,已經擁有成熟而多元的公民文化,一定禁得起這種考驗。

但是經歷了納粹噩夢,浴火重生的德國,已經擁有成熟而多元的公民文化,一定禁得起這種考驗。

Can Hong Kong lead the way in Asia to a sustainable future?

HKFP_Voices: Asia’s World City also should be World Class in green leadership and become the Copenhagen of Asia. We, on China’s southern coast, with all of regional, developing Asia to our immediate East and South – are perfectly placed for such a role, writes Nigel Reading of Asynsis.

Buckminster Fuller, the renowned inventor, engineer and designer of the...

Marseille and Moscow: In praise of dirty, sexy cities: the urban world according to Walter Benjamin

In praise of dirty, sexy cities: the urban world according to Walter Benjamin

Seventy five years after his death, the Marxist philosopher’s passion for the seedier, messier delights of cities such as Marseille and Moscow are a stark reminder of how sanitised today’s urban environment is becoming

Modern Marseille is being sandblasted, primped and cultureified. Photograph: Alamy

Cities is supported by:

Rockefeller Foundation

Stuart Jeffries

Monday 21 September 2015 09.41 BSTLast modified on Monday 21 September 201521.55 BST

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share via Email

Share on Pinterest

Share on LinkedIn

Share on Google+

Shares

5,524

Comments187

Save for later

Marseille isn’t as wicked as it used to be. In 1929, the playwright and travel writer Basil Woon wrote From Deauville to Monte Carlo: a Guide to the Gay World of France, warning his respectable readers that, whatever they do, they should on no account visit France’s second city. “Thieves, cut-throats and other undesirables throng the narrow alleys and sisters of scarlet sit in the doorways of their places of business, catching you by the sleeve as you pass by. The dregs of the world are here unsifted … Marseille is the world’s wickedest port.”

Much has changed since 1929. Gay doesn’t mean what it used to mean. Marseille isn’t the world’s wickedest port, but subject to one of Europe’s biggest architectural makeover projects. It has become respectable enough to serve asEuropean Capital of Culture in 2013. Its port has been sandblasted and civilised. Throughout the city – Eurostar’s latest destination from London – there are new trams, designer hotels, luxury flats and high-rise developments.

The last of these changes is freighted with symbolism. Marseille has been overwhelmingly horizontal since Greek graders founded it 2,600 years ago, its terracotta-roofed buildings spreading inland from the bay. Now it’s going vertical, with new skyscrapers glassily returning your gaze, looking like a Mediterranean sibling for those other formerly raffish docklands made safe for business suits – London, Hamburg and Baltimore.

The worry is, as Marseille comes to look like everywhere else, it loses what made it special – the saltiness, the wickedness, the downright smelliness so off-putting to some.

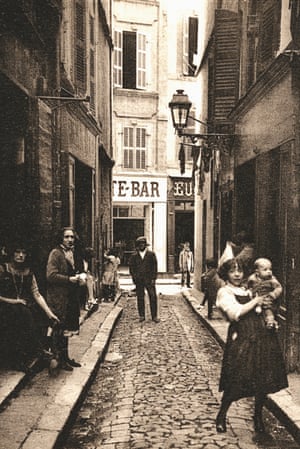

FacebookTwitterPinterest Rue de l’Amandier in Marseille, 1920. Photograph: Adoc-photos/Corbis

“Marseille – the yellow studded maw of a seal with salt water coming out between the teeth,” wrote the critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin. “When this gullet opens to catch the black and brown proletarian bodies thrown to it by ship’s companies according to their timetables, it exhales a stink of oil, urine and printer’s ink …”

Benjamin wrote these words for a newspaper article in the same same year as A Guide to the Gay World of Franceexcoriated Marseille. Unlike Basil Woon, he revelled in the city. Another French city, Toulouse, called itself la ville rose, the pink city, but for Benjamin, pink was more truly the colour of Marseille. “The palate itself is pink, which is the colour of shame here, of poverty. Hunchbacks wear it, and beggarwomen. And the discoloured women of Rue Bouterie are given their only tint by the sole pieces of clothing they wear: pink shifts.”

What Benjamin wrote about cities in newspaper essays in the 1920s and early 1930s, as well as in his book about 19th-century Paris, The Arcades Project, remains fascinating and instructive, and not just because he was one of the first thinkers to suggest that urban living intensified feelings of isolation and atomisation.

What makes this German Jewish philosopher even more compelling is that he also found the opposite in cities – flashes of the utopian in the abject – and realised they could provide solutions to, as well be the causes of, alienation. This oddball communist from segregated Berlin interpreted cities such as Marseille, Moscow and Naples as kinds of laboratories that, just possibly, suggested how we might live better.

In his essay Hashish in Marseille, Benjamin described an evening wandering from cafe to cafe after taking the drug (the philosopher stoned): “I now suddenly understood how to a painter – had it not happened to Rembrandt and many others? – ugliness could appear as the true reservoir of beauty, better than any treasure cask, a jagged mountain with all the inner gold of beauty gleaming from the wrinkles, glances, features.” Benjamin encountered in his Marseille trance what his beloved Baudelaire had found when taking the same drug in Paris nearly 70 years before: an artificial paradise.

Marseille isn’t France. Marseille isn’t Provence. Marseille is the worldRobert Guédiguian

But the Marseille Benjamin savoured, and that scared Woon, scarcely exists any more. The red-light district of the Rue Bouterie survives only as collectable postcards from the wicked era of the later 1920s. So too Basso’s, one of the restaurants in which Benjamin dined that night, nearly nine decades ago, to stave off the munchies. As I wander the Marseille streets trying, and failing, to follow Benjamin’s footsteps, I’m disappointed: the people are insufficiently ugly. Perhaps if I’d been on hashish like Benjamin …

A different Marseille – sandblasted, primped and cultureified – is rising in its place. On the Quai d’Arenc, where once Benjamin found beauty in ugliness, an old silo building has been repurposed as a 2,000-seater auditorium. Elsewhere, an old chateau has been converted into the Centre for Mediterranean Cinematography, a Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations and, my personal favourite, a museum devoted to La Marseillaise, the French national anthem where, depending on your taste, you can hear Serge Gainsbourg croaking a reggae version of Stephane Grappelli.

But the worry here is that what Benjamin’s colleagues of the Frankfurt School – Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer – excoriated as “the culture industry” becomes a means of ripping the soul out of the place while making it look as though the opposite is happening. Without being unduly cynical, culture has become part of capitalism’s sanitising redevelopment of one of the most cherishably wicked of world cities.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Zaha Hadid’s 147-metre-high Tour French Line tower rises above Marseille. Photograph: Jose Nicolas/L'Oeil du spectacle/Corbis

The focus of that redevelopment, Euroméditerranée, is among the biggest renovations schemes in Europe. It echoes what Marseille’s twin city of Hamburg is doing at HafenCity – the German port’s former docks – and similarly risks making the raffish respectable, the salty sweet, the wicked merely nice. That, so often, has been the fate of docklands redevelopments: think of London’s Docklands now devoid of opium dens and free-swearing dockers. It risks, that is to say, obliterating everything Benjamin liked about Marseille.

New Marseille is typified by Zaha Hadid’s 147m-tall Tour French Line, the corporate headquarters for shipping container company CMA-CGM. Jean Nouvel has designed three more skyscrapers for the city which, to sceptics, are excellent ways of making Marseille lose its identity.

According to the French film director Robert Guédiguian, who sets most of his films (including Marius et Jeannette and La Ville est Tranquille) in and around his home city: “All that squeezes itself between the buildings, that insinuates itself between the architectural drawings and political plans, must be carefully preserved because it is there that one finds the city’s future.”

For Guédiguian, what squeezes itself between these plans is a much more interesting city – a multi-ethnic metropolis that includes 120,000 north African immigrants whose presence has led to Marseille being called Sahara on Sea. “Marseille isn’t France. Marseille isn’t Provence. Marseille is the world,” says Guédiguian.

So what would Walter Benjamin have made of the new city that is rising over the traces of the one he loved? What’s striking about his vision of the former city is how sensitive he was to false utopianism, to the bulldozing of the past and the dreams of progress.

Benjamin was always drawn to outmoded utopias – the formerly state-of-the-art technology, the ruins of progress …

FacebookTwitterPinterest Le Passage Choiseul shopping arcade in Paris, circa 1900. Photograph: Roger-Viollet/AFP

The Arcades Project – that great ruin of a book he spent the last decade of his life assembling, until his suicide in Spain 75 years ago this month while on the run from the Nazis – focuses on the fading arcades of 19th-century Paris, in which once-fashionable shops, goods and building styles hung on briefly before Baron Haussmann destroyed them in favour of a yet-newer Paris. Benjamin was always drawn to these outmoded utopias, the formerly state-of-the-art technology, the ruins of progress – since they encoded, he thought, the delusions that capitalism instilled in its victims.

“Capitalism,” Benjamin wrote in 1922, “is a purely cultic religion, perhaps the most extreme that ever existed.” By that, in part, he meant that capitalism abases us before the new, subdues us not with opium but with must-have commodities. And cities could be shrines to the cult, too.

To get a sense of this, simply take the tourist boat trip from the Vieux Port along the coast to see the legendary Chateau d’If (where the Count of Monte Cristo was incarcerated) and the Calanques (the limestone cliffs that plunge into the Mediterranean). Look back and you’ll see a city skyline that did not exist when Benjamin and Woon wrote. Since 1864, the city was dominated by Notre Dame de la Garde, standing high on a hill on the site of a former fort. Now though, it rhymes with Zaha Hadid’s Tour French Line. The Iraqi-British architect says that her tower complements the basilica. It also, though, represents a challenge to it: hers is a glassy temple to a newer deity.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Hadid says her shipping company HQ complements Marseille’s Notre Dame de la Garde. Photograph: Hemis/Alamy Stock Photo

In promising newness, progress, built utopias, bulldozing wickedness and poverty, the development of urban landscapes could make the faithful believe more ardently in what – for a communist such as Benjamin – in fact, oppressed them. Again and again, he takes the perspective of one looking back on failed utopias, on the obsolete commodities that were once must-haves. The Benjamin scholar Max Pensky explains the political force of how Benjamin wrote about cities: “The fantasy world of material well-being promised by every commodity now is revealed as a hell of unfulfillment; the promise of eternal newness and unlimited progress … now appear as their opposite: as primal history, the mythic compulsion toward endless repetition.”

None of the above should suggest that Walter Benjamin disliked cities. Rather, he found in the ones he really liked – Marseille, Naples and Moscow in particular – antidotes to the socially zoned, ghettoised Berlin in which he had been raised around 1900.

For instance, in 1927, he took a sleigh ride through Moscow. “Where Europeans, on their rapid journeys, enjoy superiority, dominance over the masses,” he wrote, “the Muscovite in the little sleigh is closely mingled with people and things. If he has a box, a child, or a basket to take with him – for all this, the sleigh is the cheapest means of transport – he is truly wedged into the street bustle. No condescending gaze: a tender, swift brushing along stones, people and horses. You feel like a child gliding through the house on a little chair.”

Ten years after the Bolshevik Revolution, Benjamin was visiting the Soviet capital to study what he called “ the world-historical experiment”. “Each thought, each day, each life lies here as on a laboratory table,” he wrote. Riding on a Moscow tram was, for the pampered Berliner, a new experience – the poor got up close and personal. “A tenacious shoving and barging during the boarding of a vehicle usually overloaded to the point of bursting takes place without a sound and with great cordiality. (I have never heard an angry word on these occasions).”

Each thought, each day, each life lies here as on a laboratory tableWalter Benjamin on 1920s Moscow

FacebookTwitterPinterest A propeller-powered sleigh in Moscow in 1929. Photograph: Planet News Archive/SSPL/Getty Images

For a German Jew born to a wealthy family, this new experience of city life was tremendously exciting. During Benjamin’s childhood, in the exclusive suburbs of west Berlin, the poor scarcely existed, still less got close enough to jostle him on public transport. In his memoir, A Berlin Chronicle, Benjamin wrote of his upbringing that “the class that had pronounced him one of its number resided in a posture compounded of self-satisfaction and resentment that turned the district into something like a ghetto held on a lease. In any case, he was confined to this affluent neighbourhood without knowing any other. The poor? For rich children of his generation, they lived at the back of beyond.”

In the 1920s, Benjamin spent a lot of time in cities such as Moscow, Naples and Marseille – each in its different way giving him a cure to the disease of modern life in general, and the one in which he had been raised in particular. His compatriot, the German sociologist Max Weber, had written of the iron cage of capitalism inside which humans were submitted to efficiency, calculation and control. Cities were part of that system of control, which worked by keeping the poor and rich in their proper places. The cities that turned Walter Benjamin on were the opposite of that: porous labyrinths annulling class, time, space and even distinctions of light and dark.

Benjamin’s enthusiasm for these cities is, nearly 100 years on, contagious. Particularly as so many of the world’s leading cities have turned sclerotic – socially stratified cages to keep the riff raff out and the rest of us polishing our must-have Nespresso machines.

In Paris, the poor are banished beyond the périphérique so that when they revolt, they destroy their own banlieues rather than the French capital’s fussily maintained environment. London’s key workers strap-hang on laughable trains from distant commuter towns to serve the wealthy before being returned to their flats in time for the de facto curfew each day. Manhattan island is today a pristine vitrine on which the lower orders don’t even get to leave their mucky paw prints, but inside which the rich get to fulfil with unparallelled freedom their uninteresting desires. I’m exaggerating in each case, but not much. Many of the world’s leading cities are becoming like the Berlin that Benjamin called a prison, and from which he escaped whenever possible.

There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarismWalter Benjamin

FacebookTwitterPinterest The monument to Walter Benjamin in Portbou, Catalonia. In 1940 the Jewish philosopher escaped to Spain, but killed himself when he learned the authorities were likely to deport him to France and into the hands of the Nazis. Photograph: Ruth Hofshi/Alamy Stock Photo

The point of the cities Benjamin loved, by contrast, was that they broke through physical, ethnic and class barriers. In Marseille, Naples and Moscow, life was not a private commodity, but “dispersed, porous, commingled”. In Naples, about which he wrote with his Latvian lover Asja Lacis, he found private life had been effectively abolished: “What distinguishes Naples from other large cities is something it has in common with the African kraal: each private attitude or act is permeated by streams of communal life. To exist, for the northern European the most private of affairs, is here, as in the kraal, a collective matter.” He and Lacis found in Naples that “just as the living room reappears on the street, with chairs, hearth, and altar, so only much more loudly the street migrates into the living room”.

In Naples, Benjamin noted with a north European’s shock, children are up at all hours. “At midday, they then lie sleeping behind a shop counter or on a stairway. This sleep, which men and women also snatch in shady corners, is therefore not the protected northern sleep. Here, too, there is interpenetration of day and night, noise and peace, outer light and inner darkness, street and home … Poverty has brought about a stretching of frontiers that mirrors the most radiant freedom of thought.”

Is Naples today anything like the one that Benjamin and his lover eulogised? The great Italian actor Toni Servillo once told me that what he loved about Naples was that it was the world in miniature. At the time, Servillo was promoting a film called Gorbaciof, set in the Vasto, the city’s multi-ethnic district around the main railway station. And what Servillo says remains true: the great port city of Naples attracts so many immigrant communities that it can still be experienced as a messy rebuke to cities that work through de facto ethnic cleansing and social exclusion. Today, there’s a Neopolitain walking tour that takes tourists from the Senegalese market in Via Bologna, to mosques in the Pendino district, past Arab pastry shops and African hair salons, to stalls selling Maghreb crafts.

As for Benjamin, his last visit to Marseille was a bitter one. In August 1940, he found the city teeming with refugees terrified of falling into the Gestapo’s clutches. He had arrived in Marseille for an appointment at the US consulate, where he was issued with an entry visa for the United States and transit visas for Spain and Portugal.

Marseille's Muslims need their Grand Mosque – why is it still a car park?

Read more

In mid-September, Benjamin and two refugee acquaintances from Marseille decided to travel to the French countryside near the Spanish border and try to cross the Pyrenees on foot. The myopic, weak-hearted, 48-year-old philosopher made it across the border to the Catalan town of Port Bou, but then learned that the Spanish authorities were likely to return him and his fellow refugees to France – from where, most likely, they would be transferred to concentration camps and murdered.

Benjamin’s body was found in a hotel room, and it is generally thought he took a drug overdose. The inscription on his gravestone in Port Bou quotes, in German and Catalan, from one of his last essays, Theses on thePhilosophy of History: “There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

It’s an aphorism that has been interpreted many ways, not least as suggesting that the progress of capitalism was bound up with the rise of fascism. But it also can be interpreted as pertaining to what cities are.

Benjamin didn’t live in an era in which the development of new cities often means state-of-the-art golf courses fringed with fig-leaf social housing; leaf-shaped islands for the über rich that can be seen from the international space station; and gated estates expressly designed so residents can experience that same, perilously short-leased mixture of resentment and self-satisfaction that his parents enjoyed a century ago.

Nor, of course, did Benjamin live to see the attempt to purge Marseille of its wickedness. If he had, he would doubtless have seen through the ostensible civilisation to the barbarism beneath.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

2015年9月21日 星期一

Princeton's Lake Carnegie: A Place for Nature, a Scene for Activity

Take a photographic tour of Princeton's scenic and historic Lake Carnegie.

Princeton University's Lake Carnegie is one of the most open and natural...

PRINCETON.EDU

the permafrost 永久凍土帯

"These results show just how much we need urgent action to slow the melting of the permafrost."

New analysis of the effects of melting permafrost in the Arctic points to...

CAM.AC.UK

Near Arctic, Seed Vault Is a Fort Knox of Food

By ELISABETH ROSENTHAL

A vault buried under the permafrost in Norway has begun to receive millions of seeds, an effort to save the genetic legacy of vanishing plants.

vault1

vault1

━━ n. アーチ形屋根, アーチ形天井(型のもの); アーチ形天井のある場所[通廊]; 天空 (the ~ of heaven); 地下貯蔵室; 貴重品保管室; (銀行などの)金庫室; 地下納骨所; 【解】(口蓋などの)蓋(がい).

━━ vt. アーチ形天井に造る[を張る].

永久凍土帯(Pemafrost)