Angkor and Bagan, in their heydays, were among the largest and most culturally significant cities on earth.

http://s.nikkei.com/2ubXIld

http://s.nikkei.com/2ubXIld

2007.9.30

Rangoon to Yangon

English

ヤンゴン

• Have questions? Find out how to ask questions and get answers. •

Jump to: navigation, search

Yangon

officially renamed from Rangoon

Downtown Yangon, facing Sule Pagoda and Hlaing River

Yangon

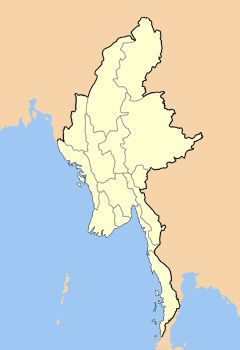

Location of Yangon, Myanmar (Burma)

Coordinates:

16°48′N 96°09′E / 16.8, 96.15

16°48′N 96°09′E / 16.8, 96.15 Country

Myanmar (Burma)

Admin. division

Yangon Division

Government

- Mayor

Brigadier General Aung Thein Lynn

Area

- City

400 sq mi (1,036 km²)

- Urban

222.4 sq mi (576 km²)

Population (2005)[1]

- City

4,107,000

- Ethnicities

Bamar, Anglo-Burmese, Burmese Chinese, Burmese Indians, Kayin

- Religions

Buddhism, Christianity, Islam

Website: www.yangoncity.com.mm

楊索我的緬甸記憶

---

緬甸蒲甘古城:歷史與未來在此交匯

報道 2012年07月13日

緬甸蒲甘——火災、洪水、尋寶者,以及榕樹輪番登場,讓這個古代王國的都城備受摧殘。但是,從很多方面而言,這裡或許仍然和800年前景象一樣。

在伊洛瓦底江的右岸一片26平方英里的乾旱平原上,有一片宏偉的佛教城市遺址,2200多座多層磚質寺廟和佛塔鱗次櫛比。這座佛教城市曾在公元11世紀到12世紀達到鼎盛。

這些遺址所在的紅土平原上,只有少數僧侶和牧羊人居住,這裡密集的寺廟建築群在世間絕無僅有,其複雜的穹頂技術,在其他亞洲文明中未曾一見。這裡的壁畫細緻精美,類似的作品未在印度得到很好的保存。

《蒲甘古國》(Ancient Pagan)和《緬甸聖地》(Sacred Sites of Burma)的作者唐納德·斯塔特納(Donald Stadtner)說,“就好像是所有哥特式大教堂都聚集在一個地方。”

經過幾十年的獨裁統治之後,緬甸終於向外部世界和蜂擁而至的遊客敞開大門。 長期以來,緬甸的政治局面將很多學者阻攔在外,現在激起學者興趣的遠遠不只蒲甘這一個地方。

早在公元前一世紀,來自中國西南部的藏緬語民族就在伊洛瓦底江上游定居,他們留下了大片有磚牆和護城河環繞的城市遺址,以及精巧灌溉系統的遺迹。

毗濕奴城是這種最早期聚居地中的一處,考古學家在那裡發現了大量的寺廟和佛塔,或稱窣堵坡。這些建築物,連同其中裝飾華麗的骨灰瓮和帶有吉祥圖案的銀幣,都與印度東部地區的佛教徒所建造的相似,說明這裡是佛教傳入東南亞的一個中轉站。

早在政治開放之前,緬甸軍政府就曾嘗試修復一些歷史遺迹,並在當地建立博物館。1975年的一場地震使蒲甘受到了極大破壞,緬甸當局於20世紀70年代末以及80年代,實施了一項重建蒲甘的浩大工程。

修復工作得到了渴望積攢功德的緬甸施主和聯合國開發計劃署(United Nations Development Program)的支持,並主要依賴國內一小圈子裡的專家。一些外國學者對於這個項目提出了尖銳批評。

批評人士認為,使用不純正的建築材料,例如用水泥代替灰泥,十分不妥,還聲稱某些建築特徵,特別是宗教建築物頂端的裝飾性尖頂,是根據想像重建的,而沒有尊重科學。幾座著名寺廟還包含了一些不協調的元素,比如圍繞佛像的頭部有迪斯科燈光在搖曳閃爍。

斯塔特納談及重建時說,“這是一場十足的災難,彷彿過去每一條考古學原則都被完全顛覆了。我想,所有人都會同意,對遺迹的破壞已經成為既成事實,而且這種破壞是不可挽回的。”

夏威夷大學(University of Hawaii)亞洲研究學教授邁克爾·昂-丁(Michael Aung-Thwin)長期研究緬甸,他認為上述批判言過其實,並聲稱這些批判是“異議人士的宣傳言論。”

“鑒於他們資源有限,他們已經取得了巨大的進展,”昂-丁博士說。

上世紀90年代擔任緬甸文化部長的吳溫盛(U Win Sein)辯解說,政府在修復古迹時,曾努力將古迹保護和佛教的布施與重修觀念相協調。

他在一份國有報紙上撰文指出,“這些鮮活的宗教建築受到緬甸人民高度尊崇和膜拜 。國家有責任保護、加固和修復蒲甘的所有文化遺迹,讓它們能世代永傳。”

倫敦大學(University of London)的考古學家和藝術史學家伊麗莎白·霍華德·穆爾(Elizabeth Howard Moore)說,她期望蒲甘最終能被列為世界遺產,這樣就能吸引外國學者對蒲甘產生新的興趣。蒲甘有許多研究問題仍懸而未決,包括該城佛教徒生活的性質、 蒲甘王國和鄰國的關係等。(有幾幅蒲甘的壁畫似乎是孟加拉藝術家繪製的。)

嶄新的政治氣候已經吸引了更多外國技術專家來到緬甸,幫助該國達到國際水準。緬甸文化部也積極歡迎外國學者提出建議。

穆爾博士說,“10年以前這一切都不存在。解除制裁不僅在國家層面催生了新的文化意識,而且,商業投資的增加已開始為文化和教育項目帶來各種各樣的支持。”

在伊洛瓦底江的右岸一片26平方英里的乾旱平原上,有一片宏偉的佛教城市遺址,2200多座多層磚質寺廟和佛塔鱗次櫛比。這座佛教城市曾在公元11世紀到12世紀達到鼎盛。

《蒲甘古國》(Ancient Pagan)和《緬甸聖地》(Sacred Sites of Burma)的作者唐納德·斯塔特納(Donald Stadtner)說,“就好像是所有哥特式大教堂都聚集在一個地方。”

經過幾十年的獨裁統治之後,緬甸終於向外部世界和蜂擁而至的遊客敞開大門。 長期以來,緬甸的政治局面將很多學者阻攔在外,現在激起學者興趣的遠遠不只蒲甘這一個地方。

早在公元前一世紀,來自中國西南部的藏緬語民族就在伊洛瓦底江上游定居,他們留下了大片有磚牆和護城河環繞的城市遺址,以及精巧灌溉系統的遺迹。

毗濕奴城是這種最早期聚居地中的一處,考古學家在那裡發現了大量的寺廟和佛塔,或稱窣堵坡。這些建築物,連同其中裝飾華麗的骨灰瓮和帶有吉祥圖案的銀幣,都與印度東部地區的佛教徒所建造的相似,說明這裡是佛教傳入東南亞的一個中轉站。

早在政治開放之前,緬甸軍政府就曾嘗試修復一些歷史遺迹,並在當地建立博物館。1975年的一場地震使蒲甘受到了極大破壞,緬甸當局於20世紀70年代末以及80年代,實施了一項重建蒲甘的浩大工程。

修復工作得到了渴望積攢功德的緬甸施主和聯合國開發計劃署(United Nations Development Program)的支持,並主要依賴國內一小圈子裡的專家。一些外國學者對於這個項目提出了尖銳批評。

批評人士認為,使用不純正的建築材料,例如用水泥代替灰泥,十分不妥,還聲稱某些建築特徵,特別是宗教建築物頂端的裝飾性尖頂,是根據想像重建的,而沒有尊重科學。幾座著名寺廟還包含了一些不協調的元素,比如圍繞佛像的頭部有迪斯科燈光在搖曳閃爍。

斯塔特納談及重建時說,“這是一場十足的災難,彷彿過去每一條考古學原則都被完全顛覆了。我想,所有人都會同意,對遺迹的破壞已經成為既成事實,而且這種破壞是不可挽回的。”

夏威夷大學(University of Hawaii)亞洲研究學教授邁克爾·昂-丁(Michael Aung-Thwin)長期研究緬甸,他認為上述批判言過其實,並聲稱這些批判是“異議人士的宣傳言論。”

“鑒於他們資源有限,他們已經取得了巨大的進展,”昂-丁博士說。

上世紀90年代擔任緬甸文化部長的吳溫盛(U Win Sein)辯解說,政府在修復古迹時,曾努力將古迹保護和佛教的布施與重修觀念相協調。

他在一份國有報紙上撰文指出,“這些鮮活的宗教建築受到緬甸人民高度尊崇和膜拜 。國家有責任保護、加固和修復蒲甘的所有文化遺迹,讓它們能世代永傳。”

倫敦大學(University of London)的考古學家和藝術史學家伊麗莎白·霍華德·穆爾(Elizabeth Howard Moore)說,她期望蒲甘最終能被列為世界遺產,這樣就能吸引外國學者對蒲甘產生新的興趣。蒲甘有許多研究問題仍懸而未決,包括該城佛教徒生活的性質、 蒲甘王國和鄰國的關係等。(有幾幅蒲甘的壁畫似乎是孟加拉藝術家繪製的。)

嶄新的政治氣候已經吸引了更多外國技術專家來到緬甸,幫助該國達到國際水準。緬甸文化部也積極歡迎外國學者提出建議。

穆爾博士說,“10年以前這一切都不存在。解除制裁不僅在國家層面催生了新的文化意識,而且,商業投資的增加已開始為文化和教育項目帶來各種各樣的支持。”

Bagan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a city in Burma. For the rural localities in Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia, see Bagan, Russia.

| Bagan ပုဂံ Pagan |

|

|---|---|

| Temples in Bagan | |

| Coordinates: 21°10′N 94°52′E | |

| Country | Burma |

| Region | Mandalay Region |

| Founded | mid-to-late 9th century |

| Area | |

| • Total | 104 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Ethnicities | Bamar |

| • Religions | Theravada Buddhism |

| Time zone | MST (UTC+6.30) |

The Bagan Archaeological Zone is a main draw for the country's nascent tourism industry.

Contents |

Etymology

Bagan is the present-day standard Burmese pronunciation of the Burmese word Pugan (ပုဂံ), derived from Old Burmese Pukam (ပုကမ်). Its classical Pali name is Arimaddana-pura (အရိမဒ္ဒနာပူရ, lit. "the City that Tramples on Enemies"). Its other names in Pali are in reference to its extreme dry zone climate: Tattadesa (တတ္တဒေသ, "parched land"), and Tammadipa (တမ္မဒီပ, "bronzed country").[1]History

9th to 13th centuries

Main article: Pagan Kingdom

According to the Burmese chronicles, Bagan was founded in the second century CE, and fortified in 849 CE.[2] Mainstream scholarship however holds that Bagan was founded in the mid-to-late 9th century by the Mranma (Burmans), who had recently entered the Irrawaddy valley from the Nanzhao Kingdom. It was among several competing Pyu city-states until the late 10th century when the Burman settlement grew in authority and grandeur.[3]From 1044 to 1287, Bagan was the capital as well as the political, economic and cultural nerve center of the Pagan Empire. Over the course of 250 years, Bagan's rulers and their wealthy subjects constructed over 10,000 religious monuments (approximately 1000 stupas, 10,000 small temples and 3000 monasteries)[4] in an area of 104 square kilometres (40 sq mi) in the Bagan plains. The prosperous city grew in size and grandeur, and became a cosmopolitan center for religious and secular studies, specializing in Pali scholarship in grammar and philosophical-psychological (abhidhamma) studies as well as works in a variety of languages on prosody, phonology, grammar, astrology, alchemy, medicine, and legal studies.[5] The city attracted monks and students from as far as India, Ceylon as well as the Khmer Empire.

The culture of Bagan was dominated by religion. The religion of Bagan was fluid, syncretic and by later standards, unorthodox. It was largely a continuation of religious trends in the Pyu era where Theravada Buddhism co-existed with Mahayana Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, various Hindu (Saivite, and Vaishana) schools as well as native animist (nat) traditions. While the royal patronage of Theravada Buddhism since the mid-11th century had enabled the Buddhist school to gradually gain primacy, other traditions continued to thrive throughout the Pagan period to degrees later unseen.[5]

The Pagan Empire collapsed in 1287 due to repeated Mongol invasions (1277–1301). Recent research shows that Mongol armies may not have reached Bagan itself, and that even if they did, the damage they inflicted was probably minimal.[6] However, the damage had already been done. The city, once home to some 50,000 to 200,000 people, had been reduced to a small town, never to regain its preeminence. The city formally ceased to be the capital of Burma in December 1297 when the Myinsaing Kingdom became the new power in Upper Burma.[7][8]

14th to 19th centuries

Bagan survived into the 15th century as a human settlement,[9] and as a pilgrimage destination throughout the imperial period. A smaller number of "new and impressive" religious monuments still went up to the mid-15th century but afterward, new temple constructions slowed to a trickle with less than 200 temples built between the 15th and 20th centuries.[4] The old capital remained a pilgrimage destination but pilgrimage was focused only on "a score or so" most prominent temples out of the thousands such as the Ananda, the Shwezigon, the Sulamani, the Htilominlo, the Dhammayazika, and a few other temples along an ancient road. The rest—thousands of less famous, out-of-the-way temples—fell into disrepair, and most did not survive the test of time.[4]For the few dozen temples that were regularly patronized, the continued patronage meant regular upkeep as well as architectural additions donated by the devotees. Many temples were repainted with new frescoes on top of their original Pagan era ones, or fitted with new Buddha statutes. Then came a series of state-sponsored "systematic" renovations in the Konbaung period (1752–1885), which by and large were not true to the original designs—some finished with "a rude plastered surface, scratched without taste, art or result". The interiors of some temples were also whitewashed, such as the Thatbyinnyu and the Ananda. Many painted inscriptions and even murals were added in this period.[10]

20th century to present

Many of these damaged pagodas underwent restorations in the 1990s by the military government, which sought to make Bagan an international tourist destination. However, the restoration efforts instead drew widespread condemnation from art historians and preservationists worldwide. Critics are aghast that the restorations paid little attention to original architectural styles, and used modern materials, and that the government has also established a golf course, a paved highway, and built a 61-meter (200-foot) watchtower. Although the government believed that the ancient capital's hundreds of (unrestored) temples and large corpus of stone inscriptions were more than sufficient to win the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site,[14] the city has not been so designated, allegedly mainly on account of the restorations.[15]

Bagan today is a main tourist destination in the country's nascent tourism industry, which has long been the target of various boycott campaigns. The majority of over 300,000 international tourists to the country in 2011 are believed to have also visited Bagan. Several Burmese publications note that the city's small tourism infrastructure will have to expand rapidly even to meet a modest pickup in tourism in the following years.

Geography

The Bagan Archaeological Zone, defined as the 13 x 8 km area centered around Old Bagan, consisting of Nyaung U in the north and New Bagan in the south,[14] lies in the vast expanse of plains in Upper Burma on the bend of the Irrawaddy river. It is located 290 kilometres (180 mi) southwest of Mandalay and 700 kilometres (430 mi) north of Yangon. Its coordinates are 21°10' North and 94°52' East.Climate

Bagan lies in the middle of the "dry zone" of Burma, the region roughly between Shwebo in the north and Pyay in the south. Unlike the coastal regions of the country which receive annual monsoon rainfalls exceeding 2500 mm, the dry zone gets little precipitation as it is sheltered from the rain by the Rakhine Yoma mountain range in the west. The average temperatures at Bagan exceed 30°C year round, and over 35°C in summer months of late February to mid May.| [hide]Climate data for Bagan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32 (90) |

35 (95) |

36 (97) |

37 (99) |

33 (91) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32.4 (90.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

22 (72) |

19 (66) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Source: www.holidaycheck.com[16] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

Bagan stands out not only for the sheer number of religious edifices but also for the magnificent architecture of the buildings, and their contribution to Burmese temple design. The Bagan temple falls into one of two broad categories: the stupa-style solid temple and the gu-style (ဂူ) hollow temple.Stupas

Evolution of the Burmese stupa: Bawbawgyi Pagoda (7th century Sri Ksetra)

Bupaya (pre-11th century)

The Lawkananda (pre-11th century)

The Shwezigon (11th century)

The Dhammayazika (12th century)

The Mingalazedi (13th century)

Originally, a Indian/Ceylonese stupa had a hemispheric body (Pali: anda, "the egg") on which a rectangular box surrounded by a stone balustrade (harmika) was set. Extending up from the top of the stupa was a shaft supporting several ceremonial umbrellas. The stupa is a representation of the Buddhist cosmos: its shape symbolizes Mount Meru while the umbrella mounted on the brickwork represents the world's axis.[19]

The original Indic design was gradually modified first by the Pyu, and then by Burmans at Bagan where the stupa gradually developed a longer, cylindrical form. The earliest Bagan stupas such as the Bupaya (c. 9th century) were the direct descendants of the Pyu style at Sri Ksetra. By the 11th century, the stupa had developed into a more bell-shaped form in which the parasols morphed into a series of increasingly smaller rings placed on one top of the other, rising to a point. On top the rings, the new design replaced the harmika with a lotus bud. The lotus bud design then evolved into the "banana bud", which forms the extended apex of most Burmese pagodas. Three or four rectangular terraces served as the base for a pagoda, often with a gallery of terra-cotta tiles depicting Buddhist jataka stories. The Shwezigon Pagoda and the Shwesandaw Pagoda are the earliest examples of this type.[19] Examples of the trend toward a more bell-shaped design gradually gained primacy as seen in the Dhammayazika Pagoda (late 12th century) and the Mingalazedi Pagoda (late 13th century).[20]

Hollow temples

|

|

|

"One-face"-style Gawdawpalin Temple (left) and "four-face" Dhammayangyi Temple

|

||

Innovations

Although the Burmese temple designs evolved from Indic, Pyu (and possibly Mon) styles, the techniques of vaulting seem to have developed in Bagan itself. The earliest vaulted temples in Bagan date to the 11th century while the vaulting did not become widespread in India until the late 12th century. The masonry of the buildings shows "an astonishing degree of perfection", where many of the immense structures survived the 1975 earthquake more or less intact.[19] (Unfortunately, the vaulting techniques of the Bagan era were lost in the later periods. Only much smaller gu style temples were built after Bagan. In the 18th century, for example, King Bodawpaya attempted to build the Mingun Pagoda, in the form of spacious vaulted chambered temple but failed as craftsmen and masons of the later era had lost the knowledge of vaulting and keystone arching to reproduce the spacious interior space of the Bagan hollow temples.[18])Another architectural innovation originated in Bagan is the Buddhist temple with a pentagonal floor plan. This design grew out of hybrid (between one-face and four-face designs) designs. The idea was to include the veneration of the Maitreya Buddha, the future and fifth Buddha of this era, in addition to the four who had already appeared. The Dhammayazika and the Ngamyethna Pagoda are examples of the pentagonal design.[19]

Notable cultural sites

| Name | Picture | Built | Sponsor(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ananda Temple |  |

1105 | King Kyansittha | One of the most famous temples in Bagan |

| Bupaya Pagoda |  |

c. 850 | King Pyusawhti | In Pyu style; original 9th century pagoda destroyed by the 1975 earthquake; completely rebuilt, now gilded |

| Dhammayangyi Temple |  |

1167–1170 | King Narathu | Largest of all temples in Bagan |

| Dhammayazika Pagoda |  |

1196–1198 | King Sithu II | |

| Gawdawpalin Temple |  |

c. 1211–1235 | King Sithu II and King Htilominlo | |

| Gubyaukgyi Temple (Wetkyi-in) | Early 13th Century | King Kyansittha | ||

| Gubyaukgyi Temple (Myinkaba) |  |

1113 | Prince Rajakumar | |

| Htilominlo Temple |  |

1218 | King Htilominlo | Three stories and 46 meters tall |

| Lawkananda Pagoda |  |

c. 1044–1077 | King Anawrahta | |

| Mahabodhi Temple | c. 1218 | King Htilominlo | Smaller replica of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya | |

| Manuha Temple |  |

1067 | King Manuha | |

| Mingalazedi Pagoda |  |

1268–1274 | King Narathihapate | |

| Minyeingon Temple |  |

|||

| Myazedi inscription |  |

1112 | Prince Yazakumar | "Rosetta Stone of Burma" with inscriptions in four languages: Pyu, Old Mon, Old Burmese and Pali |

| Nanpaya Temple |  |

c. 1160–1170 | Hindu temple in Mon style; believed to be either Manuha's old residence or built on the site | |

| Nathlaung Kyaung Temple |  |

c. 1044–1077 | Hindu temple | |

| Payathonzu Temple |  |

c. 1200 | in Mahayana and Tantric-styles | |

| Seinnyet Nyima Pagaoda and Seinnyet Ama Pagoda | c. 11th century | |||

| Shwegugyi Temple |  |

1131 | King Sithu I | Sithu I was assassinated here; known for its arched windows |

| Shwesandaw Pagoda | c. 1070 | King Anawrahta | ||

| Shwezigon Pagoda |  |

1102 | King Anawrahta and King Kyansittha | |

| Sulamani Temple |  |

1183 | King Sithu II | |

| Tharabha Gate |  |

c. 1020 | King Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu and King Kyiso | The only remaining part of the old walls; radiocarbon dated to c. 1020[22] |

| Thatbyinnyu Temple |  |

c. 1150 | Sithu I | At 61 meters, the tallest temple in Bagan |

| Tuywindaung Pagoda | Anawrahta |

Museums

- The Bagan Archaeological Museum: The only museum in the Bagan Archaeological Zone, itself a field museum a millennium old. The three-story museum houses a number of rare Bagan period objects including the original Myazedi inscriptions, the Rosetta stone of Burma.

- Anawrahta's Palace: It was rebuilt in 2003 based on the extant foundations at the old palace site.[23] But the palace above the foundation is completely conjectural.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。