9 Top Architects Share Their Dream Projects to Improve (or Save) New York City

As the year draws to a close, it’s time to think ahead on how to improve the city. The Regional Plan Association had its macro-proposals (though its notion of shutting down the subways at night to repair them didn’t go over too well). But clearly something — many things — ought to be done. So we asked some of New York City’s most innovative architects how they’d like to fix this place up a bit. Or just possibly, in the face of climate change, keep our great metropolis from being swamped. The suggested city renovations that came back ranged from whimsical to apocalyptic, minor touch-ups to epic engineering undertakings, depending on the temperament of the particular designer.

East River Valley

If there’s one unavoidable message we’ve been taught this year, it’s that climate change is coming for our cities. Not that this should have been news: Five years before Houston went under and swaths of Los Angeles burned, Sandy showed New York what we can expect more of, more often. In response, a team led by architect Bjarke Ingels was commissioned by the city to plan a “Big U” set of defenses around Manhattan, composed of parks and berms and sea walls, from midtown to downtown. Architect Mark Foster Gage, whose work seems to take inspiration from the enchanted and/or dystopian CGI megalopolises of fantasy films, dismisses such a defense system as merely a “fun U-shaped park” that in any case won’t do anything to protect the shorelines of Brooklyn and Queens. He stresses instead that “epic-scale thinking is required.” And so, Gage proposes draining the East River and plugging it up with enormous dams, allowing the city and its residents to use the revealed riverbed for parkland, food production, and the construction of “massive, next-generation, geothermal wells to power the next century of the city’s energy needs.” It’s certainly fanciful, but Gage says that the alternative is “to watch the coming floods wash away our city, our future, and hopefully all evidence of our shortsighted complacency.”

Ewok NYC

Charles Renfro of Diller Scofidio + Renfro took the lessons learned from working on the High Line to imagine creating a citywide network of rooftop parks: “Delicate bridges could fly over streets, linking lush islands of green in the sky.” And “planted surfaces are not only appealing aesthetically, but also absorb summer heat and storm water, problems that will only get worse the deeper we get into global warming. They are also elevated and resist flooding by definition.” Some of them could even become “elevated campgrounds … A blanket of Burning Man at 45 feet.” Who wouldn’t want New York to be more like the ewok village?

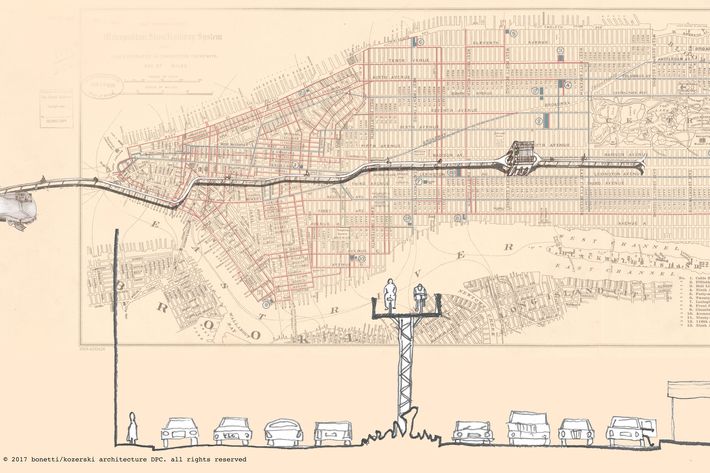

El Bike Lanes

Bonetti/Kozerski Architecture came up with the idea of “the El Bike Lanes,” which would “save pedestrians from the fierce bicycle swarms that run through the city” (and the bikers, of course, from the pedestrians and crazed Uber drivers), while also providing a low, swooping viaduct from the Battery across the harbor to Governors Island. They foresee it being integrated with the Citi Bike system, too.

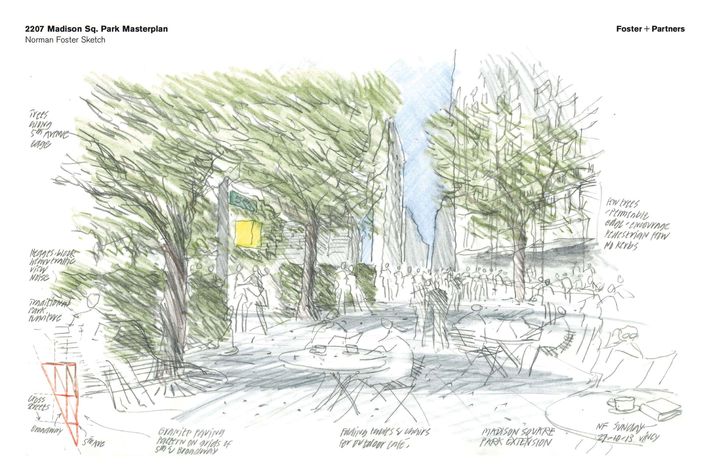

Piazza Flatiron

Norman Foster would love to extend Madison Square Park. “The project embraces New York’s strategy to gain space for pedestrians. In the junction of Broadway and Fifth Avenue, General Worth Square is a precious urban space followed by a series of off-traffic islands currently disconnected. The scheme intends to stitch all these together by providing one single language for all: granite paving pattern and reinstated trees — as Worth Square once had — along edges to screen-off traffic. The result is an extension to the adjacent Madison Square Park beyond the Flatiron building, which would materialize old aspirations of the surrounding neighbors claiming a place to meet together as a community.” It could also conceivably help accommodate extra-long Shake Shack lines.

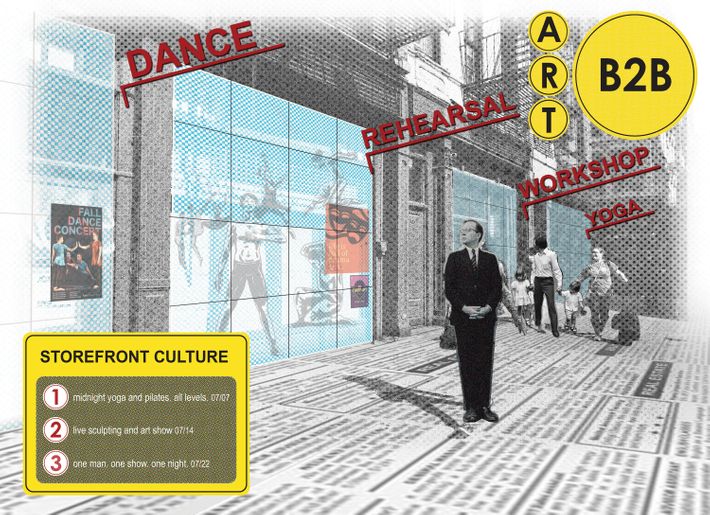

Shopbnb

David Rockwell wants to rethink how the city’s storefronts can be used. As street-level retail continues its retreat from the steady advance of the Amazon Army, he feels that storefronts — “the heart of the life of the street” — should be treated more like we do public space, like parks, squares, and sidewalks. “Walking around Soho, I’m struck by the number of beautiful but empty storefronts that are covered with brown paper and ‘for lease’ signage,” he says. “It’s a heavily trafficked area, and that’s a lot of public-facing space that isn’t serving anyone.” So inspired by his work creating theater sets, Rockwell realized that “it’s possible to create impact and memory without massive infrastructure. The solution doesn’t need to be monolithic, and it doesn’t need to last forever.” His idea? “There should be a database of available storefronts that creatives can book on demand for public performances, rehearsal spaces, and events: a cultural Airbnb, with rentals at reduced-to-no cost. An app could advertise location-based spaces for artists, as well as what’s going on that night for audiences. It’d be real spaces in real time. The city could offer incentives to landlords to make these storefronts available on a temporary basis. On Thursday, a shuttered shop could morph into a writer’s workshop or a dance studio; on Saturday, it could host a one-man show. If we can get a meal or hotel room or car on demand, why not public space? Why not theater and art? And why not all of them, all at the same time?”

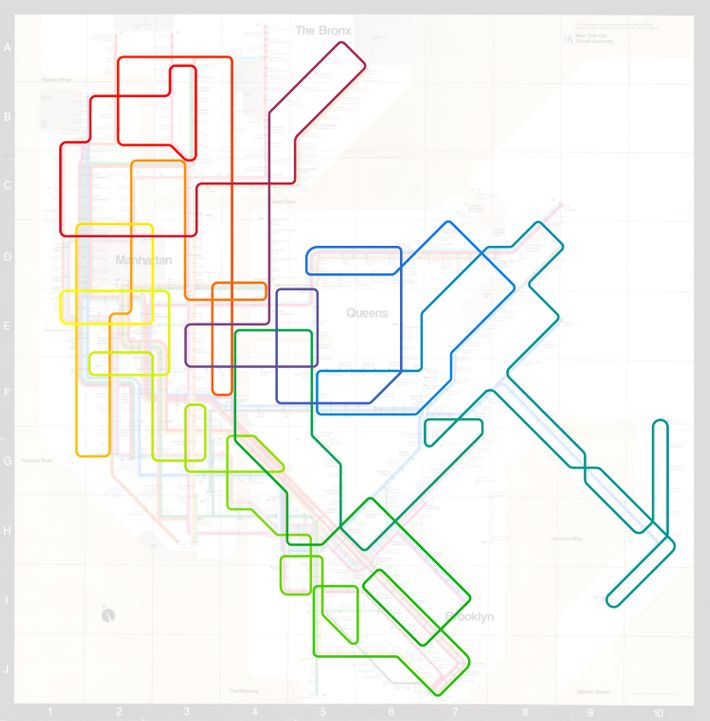

The Subway That Never Ends

Rafael de Cárdenas imagines connecting our dead-end subways into one continuous, graceful, unified loop, extrapolating poetically off of Massimo Vignelli’s iconic 1972 subway map.

Super-Tall Parasite Parks

Oana Stanescu and Dong-Ping Wong, of Family New York, suggest that the city’s new skyscrapers should be required to be better citizens. “There are currently 20 super-tall towers planned for New York, almost all of them dedicated to luxury residential, just like a three-dimensional chart of wealth. A third of these towers will remain empty for the majority of time, inhabited by expensive furniture for ghosts. But what if the new skyline wasn’t just an exclusive club for the super rich?” Stanescu asks. What if this new skyline was accessible to all? What if civic, educational, recreational, and cultural programs — programs that make this city better for everybody — were part of the transformation of New York City’s profile?” Requiring public space in the new buildings would make the city better for the rest of us, who otherwise must just cower in their very expensive shadows.

Vertical Streets

Rafael Viñoly proposes moving on from the city as a “celebration of verticality.” Since “what makes it so amazing is all this density, in a relatively small rocky island, which has created this urban experiment that’s unique and irreproducible,” then “the next stage, the natural one, is that this should become three-dimensional — that the streets should also be vertical, not just on the ground, but in a matrix of elevated circulation patterns. I know it sounds Buck Rogers–y, but it isn’t: It’s what we suggested in our entry for the reconstruction of the World Trade Center, a system that would enable you to navigate the city beyond the horizontal realm. The surface plane of Manhattan is exhausted, and you need to find ways where the space above you could be navigated and accessed as well. It’s bound to happen, and it connects with important things — the idea of resilience especially, what with sea levels rising.”

Apocalypse Harbor

Ferda Kolatan of SU11 Architecture+Design suggests another response to climate change, this time in the aftermath of a future catastrophic storm. He imagines “a large-scale terraforming effort to create a new landmass at the tip of Manhattan, which reaches all the way from New Jersey to Brooklyn,” after a (let’s face it, not at all unlikely) massive hurricane devastates the harbor. He calls it the New York Bay Peninsula project: “Combining landfill with infrastructure, a new peninsula emerges bridging the devastated areas and creating a barrier to protect lower Manhattan and Brooklyn from future flooding. The East River estuary becomes an inland lake with dams controlling water at Governors Island (now part of the peninsula) and Rikers Island to the north. Flooded zones west of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway are not rebuilt and left submerged, effectively turning the BQE into a miles-long dike. The peninsula provides a new vision for urbanization by merging infrastructure with housing and landscape. Large, uninhabited landmasses combine with solar and water-treatment facilities to form a more robust shoreline. In between those, a floating residential and cultural neighborhood is located. Access to it is given by ferry and through roads located on top of the flood walls. Smaller islands surround the peninsula serving as water barriers and providing new programmatic spaces for New York.”

Additional architect-wrangling by Ian Volner.

*A version of this article appears in the December 25, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

沒有留言:

張貼留言