He’s fed up of phallic towers, had enough of space-age blobs and is really rather cross about architects scattering novelty shapes across his great cities with reckless abandon. China’s president, Xi Jinping, has called for an end to the light-headed lunacy of weird buildings that have been spawned by the country’s construction boom over the last decade, crowding out skylines with enormous golden eggs and big pairs of pants.

In a two-hour speech at a literary symposium in Beijing last week, Xi said that art should serve the people, and called for morally-inspiring architecture that should “be like sunshine from the blue sky and the breeze in spring that will inspire minds, warm hearts, cultivate taste and clean up undesirable work styles.”

Over the last few years, China’s accelerated urban growth, paired with the emergence of a billionaire business class keen to make its mark, has created a fertile playground for western architects. Lured by the scale of ambition and sheer speed of building, they have been allowed to indulge in fantasies they could never get away with back home, egged on by cut-price construction costs and safely distanced from the cruel realities of migrant labour conditions.

Cities have also seen the results of a newly liberated home-grown creative class, allowed to unleash its talents on a scale never seen before. The state-owned architectural institutes have also been infected with a taste for the iconic and exotic, while provincial business magnates continue to do their thing with brassy flair.

Take a look at some of the strangest species this warp-speed architectural laboratory has produced.

SPACE EGGS

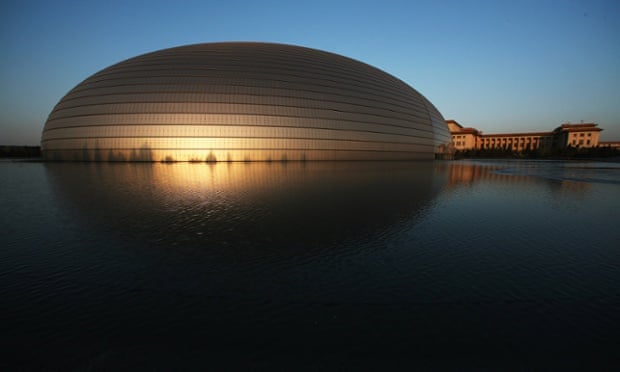

National Centre for the Performing Arts, Beijing

Designed by French architect Paul Andreu, Beijing’s opera house was one of the first specimens of the space-egg genre to arrive in China. It landed next to Tiananmen Square in 2007 like the freshly-laid produce of some gigantic robo-chicken, plopped into a lake. An unlikely success story, given that most Chinese insults revolve around eggs, its ellipsoid titanium dome would go on to inspire a generation of architects with egg-shaped ambitions.

Galaxy Soho, Beijing

Not to be outdone by a Frenchman, queen of the space egg Zaha Hadid soon laid a clutch of stripy white eggs a little further east, conjoined by rippling ribbons of architectural albumen forming a swooping world of aerial walkways. It proved so popular with its clients, the Soho group, that they commissioned another batch of slightly more pointy eggs across town – which were then copied by a company in Chongqing before the original was even finished.

Henan Art Centre, Zhengzhou

Beijing might now have a whole basket of space eggs, but Zhengzhou, the capital of nearby Henan province, actually got there first in 2003 and went one better: golden space eggs. Designed by Canadian-based Uruguayan architect, Carlos Ott, the Henan Art Centre is apparently not inspired by eggs at all, but intended to resemble abstract versions of ancient Chinese wind instruments – the Xun (a kind of ocarina), the panpipes and the bone-flute.

Phoenix Island, Hainan

Like a cluster of sailing boats undergoing some kind of warp-drive, these globular totems are the work of China’s own spawn of Zaha, Ma Yansong of MAD Studio. Part of a luxury artificial archipelago, built off the coast of Hainan Island in southern China, the development was billed as “China’s Dubai,” proclaimed to be a “fierce competitor” for the title of “eighth wonder of the modern world.” Butreports say that it’s rapidly turning into a ghost island, as investors rush to offload their apartments following the economic downturn.

Linda Haiyu Plaza, Beijing

More of a space caterpillar than an egg (although its designers claim it resembles a fish), the Linda Haiyu Plaza squats at the corner of Beijing’s Fourth Ring Road, ready to swallow you into its gaping mouth. It takes the futuristic costume of Zaha Hadid’s Soho projects and stretches it over a series of bloated office towers, like an overweight businessman squeezed into a raunchy spandex leotard.

OBJECTECTURE

Tianzi Hotel, Hebei

China has a fine history of carving enormous buddhas into mountainsides, and one hotel entrepreneur has been keen to keep up the tradition, erecting a vast trio of habitable gods in the middle of Hebei, east of Beijing. The building takes the form of 10-storey high effigies of Fu, Lu and Shou, the Chinese gods of good fortune, prosperity and longevity. Shou, the beaming chap with the white beard, welcomes guests through a door in his right foot, while his right hand holds the Peach of Immortality – which houses the hotel’s best suite.

Wuliangye Yibin building, Sichuan

It only seems appropriate that the producer of China’s most potent white spirit, baijiu, has chosen to monumentalise its liquor in the form of a gigantic bottle building. Indeed, the whole of its factory and visitor complex in Yibin, Sichuan province, is conceived as an alcoholic Alice in Wonderland theme park, with buildings in the shape of the drink packaging and avenues lined with glistening oversized bottles.

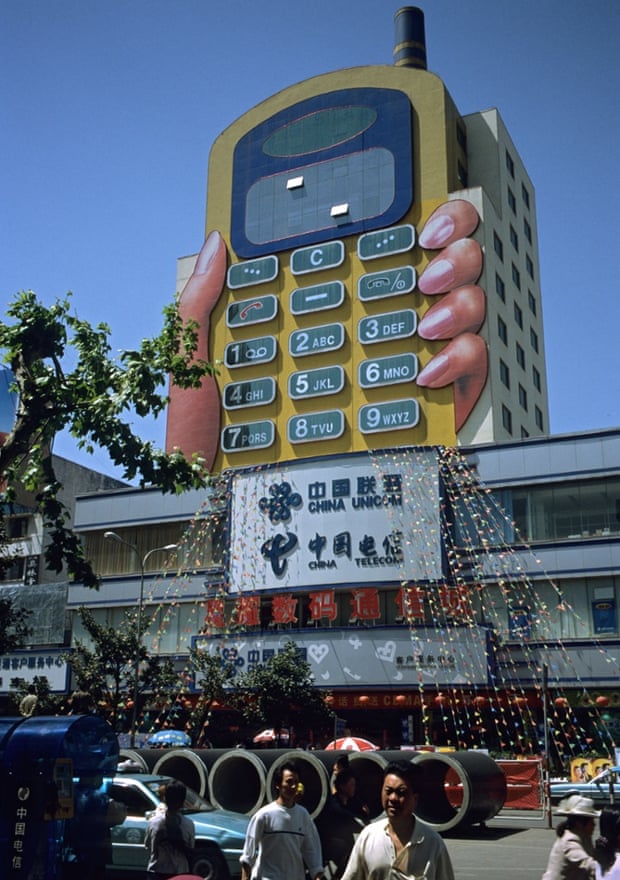

Mobile phone building, Kunming

London might have its own building-sized homage to the phone handset, in the form of the death-ray wielding Walkie-Talkie, but in southern China’s Yunnan province they do things much more literally. Rising above Huancheng Road in the provincial capital Kunming, the 11-storey mobile phone building features button-shaped windows and a penthouse office floor that looks out through the screen – plus a sinister blue hand, emerging from the ground and clutching its sides.

Piano and violin building, Huainan

No, it’s not Taylor Swift’s dream mansion, but an experimental building in Huainan, central Anhui province, designed by a group of architecture students at Hefei University of Technology. Conceived as a rehearsal and performance space for music students at the local college, visitors enter through the glass violin atrium, before travelling up a series of escalators into the bowels of the piano, and on to a roof terrace, shaded by the propped-open lid. Locals have allegedly dubbed it “the most Romantic building in China” – though perhaps they don’t know that it currently serves as a showroom for the city planners.

Teapot building, Wuxi

What shape does a tourist information centre take in an area famous for its red clay teapots? A teapot of course, made all the more spectacular by having been funded by the second richest man in China, Wang Jianlin of the Dalian Wanda group – which is eagerly buying up chunks of London. The 10-storey pot in Wuxi, Jiangsu province, has received the blessings of antique teapot master Wang Jinchuan, who praised the building’s design as “strongly reflecting clay teapot culture”. Who’d have thought it. But if you thought all this was bonkers enough, it gets better: the whole thing can rotate.

Meitan Tea Museum, Guizhou

Wuxi’s pot may rotate, but it’s not the biggest teapot building in China. That sought-after title goes to the Meitan Tea Museum in southern Guizhou province, which towers 74m as a proud symbol of the “hometown of Chinese green tea”. Coming complete with a neighbouring tea-cup building, if it were ever filled it would hold 28m litres of tea. It trounces the previous Guinness World Record for the Largest Teapot Monument (yes, there is such a category), which was set by the Chester Teapot, built by William “Babe” Devon in West Virginia in 1938 – which stands just four metres high.

Lotus building, Wujin

According to its Australian architects, Studio 505, this exhibition and conference centre in Wujin, Jiangsu province, was designed as “a giant series of lotus flowers, in varying stages of their life – from the young strong and tightly wrapped bud, to the vigorous open flower, through to the mature and fully splayed flower revealing the kernel of new life in the form of the seed pod as the third.” The architects themselves describe it as “an essay in elegance and restraint”. God knows what their other buildings look like.

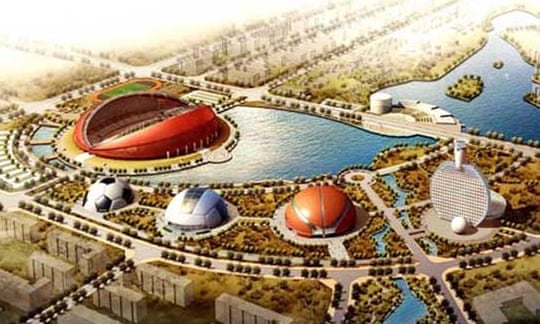

Olympic Park, Anhui

Clearly bidding to become the world capital of objectecture, already home to the piano and violin building, Huainan City launched an ambitious plan for an Olympic Park in 2011 with venues designed like a load of massive balls. There would have been a main stadium shaped like an American football, a swimming pool like a volleyball, two other stadia shaped like a football and basketball and, crowning it all, a hotel housed in a 150m tall ping-pong bat – complete with a panoramic restaurant in the handle. Deemed a profligate fancy, it prompted the chiefs of Anhui province to declare a ban on novelty buildings.

GATEWAYS

Ring of Life, Fushun

Nothing says ‘Look at our city!’ like a massive glowing circle looming above the horizon. Having abandoned plans for an office building and entertainment complex (the local population was deemed too small to support such a use), Fushun city planners settled on building an enormous empty metal ring to attract tourists to the region. Not to be mistaken for an advert for the Dyson bladeless fan, the Ring of Life houses a viewing platform and is fitted with 12,000 LED lights, making it hard to miss by night. It was originally intended to include a bungee-jumping platform at the summit, but the plan was cancelled when the ring was found to be too high to jump from. Some have speculated on other uses for the great ring.

Guangzhou Circle

As if a giant cable reel had rolled into town and come to rest on the banks of the Pearl River, Guangzhou Circle towers 138m above southern China’s largest city like a great copper spool. Housing the world’s largest stock exchange for raw plastic material, it is the work of Italian architect Joseph di Pasquale, who says the form was “inspired by the strong iconic value of jade discs and numerological tradition of feng shui.” How so? Because not only does the 50m-wide hole punched through the centre make it look like an ancient Chinese coin, but when the building is reflected in the river it forms the lucky number eight. And an infinity symbol. And the insignia of ancient dynasty that reigned in this area 2,000 years ago.

Sheraton Hotel, Huzhou

Like a large doughnut dunked halfway into the waters of Huzhou, in Zhejiang province, the Sheraton hotel is another treat from Ma Yansong and MAD Architects. The 27-storey ovoid arch apparently draws on the region’s ancient humpback bridges, only souped-up into a space-age glass and steel loop. “Huzhou itself is a place famous for traditional ink paintings and splendid water views, and the arch bridge is one of the key elements of traditional architecture,” says Ma. But he neglected to mention the inspiration of the splendid traditional outlet of Dunkin’ Donuts in the local mall.

Gate of the Orient, Suzhou

“It’s just a big pair of pants!” raged local bystanders, as the long legs of the Gate of the Orient were joined together with a majestic crotch on the skyline of the ancient city of Suzhou in 2012. Soaring 74 storeys into the clouds, the office building has been declared the largest gateway building in the world – and no doubt takes the title of the world’s largest trouser-shaped building too. Designed by British practice RMJM, who should know better, the building has been declared “humiliating” by some locals, who say walking through its gaping arch is “like being forced to crawl between someone else’s legs.”

CCTV headquarters, Beijing

While we’re on the topic of undergarments, the headquarters of China Central Television, designed by Dutch practice OMA, has drawn smutty sniggers and been nicknamed the “big boxer shorts” – as well as likened to someone squatting above the city, ready to offload a nasty surprise. It is a menacing gateway, modelled on New York’s twin towers bent double and knotted in a precipitous cantilever, and an appropriately sinister symbol of the state-controlled propagandist mouthpiece. But the form has also proved something of a hit, and has already been copied in other cities in China.

沒有留言:

張貼留言